The title and content of our first academic paper published together with my Phd colleague Marco Mason was «From Social Relevances towards Design Isses» (Eckert, Mason, 2010). After its presentation and discussion at the 6th Swiss Design Network Symposium entitled «Negotiating Futures», the correlation between design as a discipline as well as it’s manifestation in design interventions and their interdepence with frictions and conflicts that emerge within the eco-socio-political sphere stood at the core of my work as a design educator and researcher—sometimes in more evident and explicit ways and sometimes in more subtile ways when developing assessment criteria for our student’s projects and theses.

Some years later, I set out to find an appropriate term or word that would describe this mindset conveying an attitude of serving society and the ecosystem it lives in. During this quest, I came across the term «stewardship», which by the Oxford Dictionary is explained with a beautiful example:

«Farmers pride themselves on being stewards of the countryside»

And opposite to the belief that farmers are the ones producing and selling us their products, their mission, indeed, extends into being responsible for a certain part of the ecosystem that they take care of and we live in. Interestingly, this compares a lot to how designers are being perceived as people who might take decisions about the visual or physical propoerties of artefacts, while their real mission should or courld be priding themselves on being stewards of both the human and non-human entities they design for, their communities as well as the ecosystem that they live in.

«Designers should pride themselves on being stewards the human and non-human entities they design for, their communities as well as the ecosystem that they live in.»

Ever since the publication of «La Speranza Progettuale» by Tomás Maldonado (1970) and Papaneks «Design for the Real World» (1971) the topic of the social and ecological responsibility of design got highly discussed but mainly poorly implemented in design practice or the common perception of the design domain. Even design education still struggles with overcoming old paradigms and transforming its curricula to platforms forging a generation of designers as agents of eco-social transformation.

Over the years, one result of my inquiry was the mental model of the Y-shaped Designer that complements the well-known T-Shape with a connecting piece focusing on competences that are needed in order to lead collaborations across disciplines from a stewardship point of view. During the development and discussion of the Y-shaped model, I also set out to outline a first set of principles that would better define what Stewardship in Design could mean on a daily base of design practice and education. This first definition was mainly inspired by the «Aiga Designers 2025» (Aiga, 2017) statement, the «Montreal Design Declaration» (World Design Summit Organisation, 2017) and the «Lancaster Care Charter» (Rodger et al., 2017, 2019).

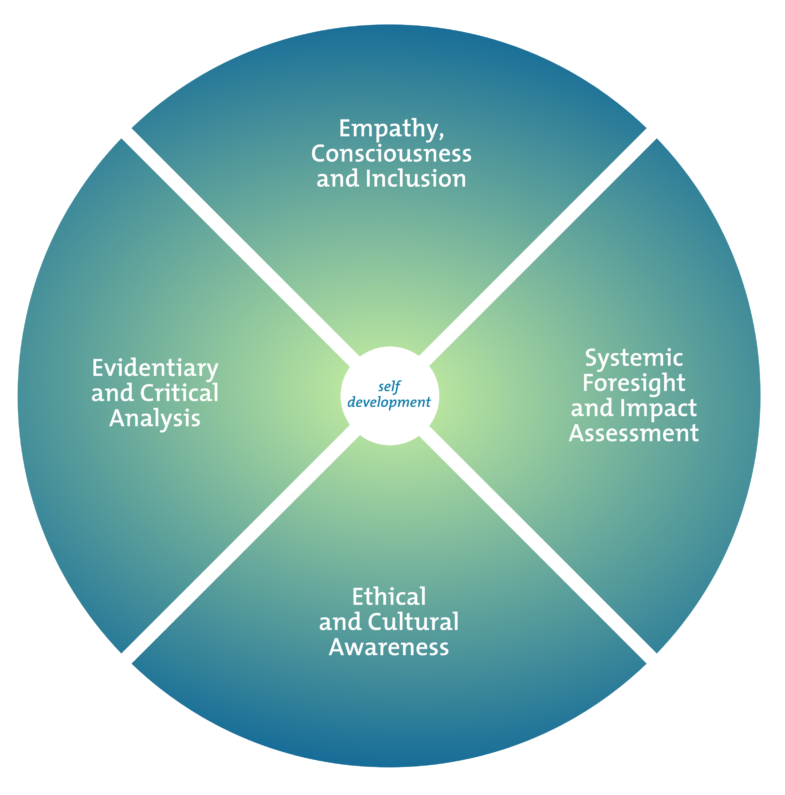

After applying the first set of principles successfully to a number of courses and curricular developments, I set out to re-arrange and reflect upon the initial list from a Systems Thinking point of view. As a result, four areas emerged that put the single aspects of the initial principles of Stewardship in Design into relationship to each other. Furthermore, these areas hold both a certain openness in terms of re-negotiation of the single aspects of Stewardship in Design as well as the character of a platform that becomes the launching point for leverage points to transform systems from different angles such as the ones laid out by environmental Scientist Donella Meadows (Meadows, Wright, 2008). The following list shows an attempt to lay out some of the parinciples and aspects that might emerge in the four areas of Stewardship in Design.

Empathy, Consciousness and Inclusion

Inclusion and Participation Whether holding a role as facilitators, when leading collective design processes or even when designing visual, physical, digital or social artefacts, designers are responsible for the active inclusion of all necessary participants.

Agility Designers embrace the openness and unfinishedness of their interventions and artefacts in order to make them inclusive and adaptive design solutions ready for future extensions or transfers across systems and/or sub-systems.

Empathetic Leadership Designers acquire leadership skills based upon empathy in order to lead cross-cultural conversations and projects. They adopt their leadership style to the stakeholder ecosystem they work in.

Transforming Consciousness and Behaviour Designers are aware that acting within systems requires an transform of consciousness and behaviour. Therefore, a systemic design intervention starts with active self-development.

Systemic Foresight and Impact Assessment

Foresight and Evaluation Designers are able to anticipate, assess and control the impact of their interventions in relationship to human and non-human entities, cultures, societies, economies and ecosystems.

Identifying Problems and Leverage Points Designers actively reveal areas of friction, conflicts and leverage points that become starting points for systemic design interventions.

Modeling and Prediction Designers embed the scenarios they develop into models based upon quantitative and qualitative data. Based upon these models designers critically examine this data by the means of predictive analysis.

Ethics and Cultural Awareness

Ethical and Cultural Awareness Designers are ethically aware that at the core of their work stands the relationship between any design intervention and its impact on the human being, non-human entities, cultures, societies, economies and the ecosystem these are embedded in.

Facilitation and Translation Designers act as facilitators and translators across sectors, disciplines, media, cultures, economies and technologies.

Evidentiary and Critical Analysis

Forensics Designers apply their capacities of combining evidence based upon soft and hard facts in a way that helps to unveil areas of friction, conflicts, issues and challenges that, then, can be addressed by the means of design.

Research Integrity and Transparency Designers embed their work into a transparent methodology, a culture of research and documentation in order to be accountable for their work and making their acting as transparent as possible towards the community.

Data literacy and De-Computation Designers are aware of data-driven processes and are able to relate to these processes as “actors of de- computation” in order to turn them into benefits for the human society and the world it lives in.

A Design Curriculum based upon Stewardship in Design

Since the attitude of Stewardship in Design already stood at the core of my educational work in design—or better: it became a sort or mindset that framed my work as a design educator—I, currently, set out to further define how the principle of acting as stewards for our socio-ecosystems could extend into a wider framework aiming at the re-design of our design curricula.

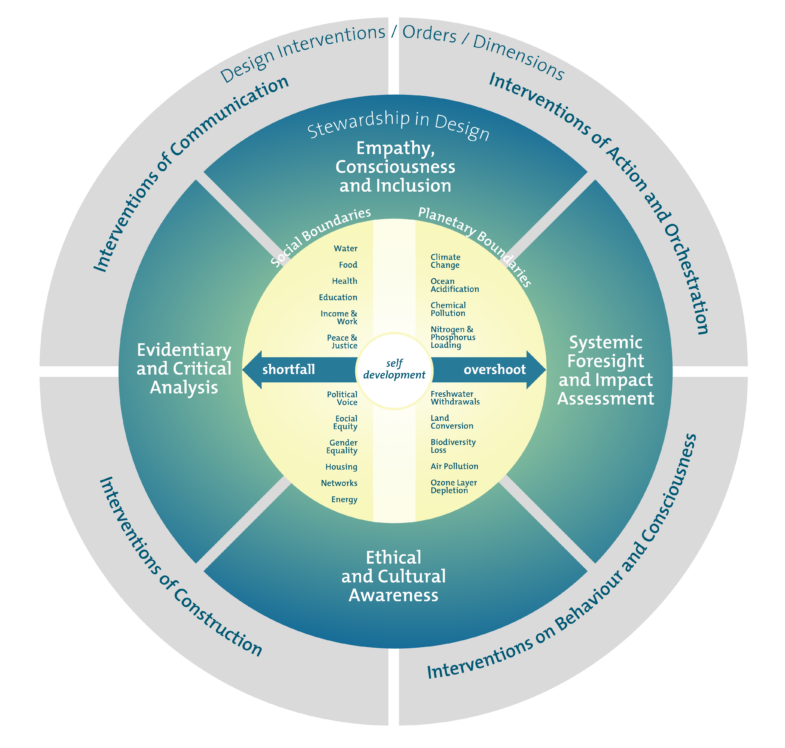

A first attempt puts the four areas that have been outlined above into the context of our Planetary and Social Boundaries as summarised in the Doughnut Economics Model by Kate Raworth (2018). In a secondary step, the concept is embedded into four further areas where Design Interventions might manifest:

- Interventions of Communication

- Interventions of Construction

- Interventions of Action and Orchestration

- Interventions on Behaviour and Consciousness

By relating to Buchanan’s Four Orders of Design, these areas try to set launchpads or directions for both identifying and addressing leverage points that might lead to systemic change in terms of transformations through design interventions.The idea behind the diagramme showed above is that learners (or researchers/practitioners) wprk their way through the model from the inside out—from the critical examination of their selves towards the holistic transformation of the systems that they are addressing.